ประเทศไทยอาจจะกลายเป็นสมาชิกใหม่ล่าสุดของสโมสรเผด็จการ

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Thailand's Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn is due to open the junta-appointed legislature on Thursday, so the military can follow normal procedure to pass new laws and spend money. But nobody should be under any illusion that this is a return to civilian government. Developments since May's coup suggest that Thailand is unlikely to return to full democracy next year as promised.

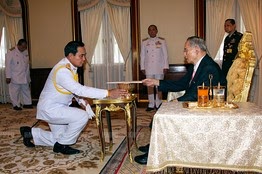

Some 115 of the National Legislative Assembly's 200 seats are occupied by military and police officers, giving the junta a working majority to pass legislation even without its civilian friends. Coup leader and army chief Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha is widely expected to be elected Prime Minister, and he will then appoint his own cabinet.

In case legislators get unruly, the real power will remain in the National Council for Peace and Order, also headed by Gen. Prayuth. The junta wrote its own provisional constitution last month, a short and vague document endorsed by King Bhumibol on July 22. Article 44 allows the NCPO to intervene and overrule any branch of government at any time if necessary for the "peace and safety of the country."

The point of this tight control is to rig Thailand's future political system to prevent supporters of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who the majority of Thai voters support, from forming a future government. The junta will appoint a 36-member drafting committee to write a new constitution, Thailand's 20th. If they fail to do so within 120 days, the committee will be disbanded and a new one appointed.

If all goes well, elections under this charter will be held in October 2015. But royalists are already mooting plans to reserve a large section of seats in both houses of parliament for appointed elites. More restrictions may also be placed on who can run for office. That will make it impossible for grass-roots populists like Mr. Thaksin to win power.

Contrast all this with the last coup in 2006, when the military took some pains to preserve a fig-leaf of due process and fairness in writing a new constitution. The coup leaders appointed a civilian government, albeit one made up in part of retired officers, and gave it a measure of autonomy. The new constitution left the House of Representatives largely democratic, but its power was checked by a half-appointed Senate and other institutions made up of self-selecting elites. The charter was put to a national referendum.

The election of Mr. Thaksin's sister Yingluck Shinawatra as Prime Minister in 2011 evidently taught the military that they should not be so concerned with democratic niceties this time around. The electorate will not get a chance to reject the next constitution, and the provisions for amendment will likely become even more formidable.

The potential for disaster in this course of action would seem obvious, since critics of the government will have little chance to replace it by democratic means. Corruption, already endemic in Thailand, has run rampant under previous undemocratic regimes.

In their antipathy to Mr. Thaksin, Thai elites have increasingly sealed themselves within an echo chamber of support for government by "good people," meaning those who agree with them. Critics are labelled paid lackeys of the enemy and anti-Thai. This extends even to the U.S. and other Western governments that have mildly criticized the junta's behavior, withdrawn some aid and called for a quick return to democracy.

Not surprisingly, China is taking advantage of this situation. Beijing pledges support for the junta's efforts to restore "stability," and in return the generals have restarted a high-speed rail project to connect the two countries. As next-door Burma slips from Beijing's orbit and democratizes, Thailand could become the newest member of the authoritarian club.